Jurisdiction: Sierra Leone

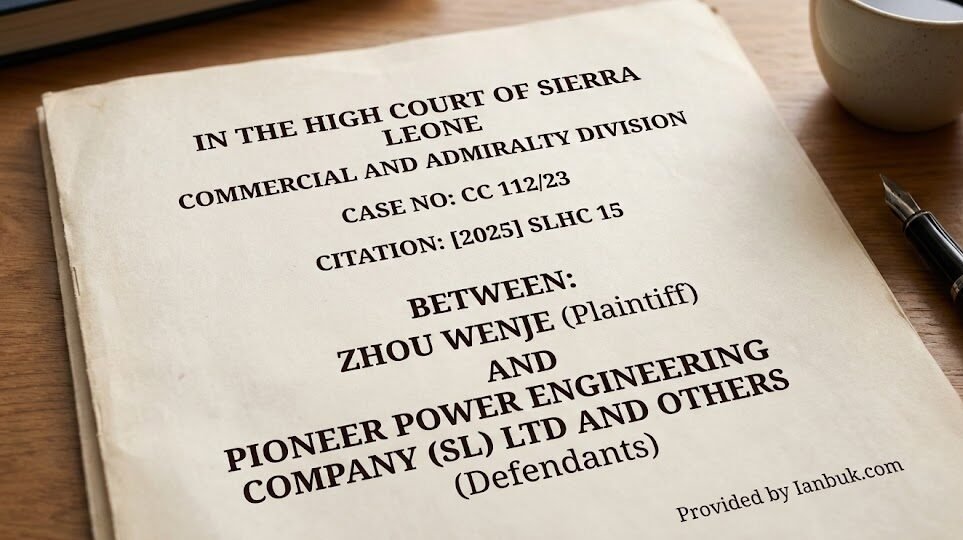

Court: High Court of Sierra Leone, Holden at Freetown, Commercial and Admiralty Division (General Civil Division heading appears on the face page)

Presiding Judge: The Honourable Mr Justice Fisher J

Hearing date: 5 March 2025

Date of judgment (as stated on the face page): 12 June 2025

Neutral citation: Misc.App/001/25 W1

Case number: Misc.App 001/25

Parties: Zhou Wenje (Applicant) v Pioneer Power Engineering Company (SL) Ltd (Respondent), Attorney General and Minister of Justice (1st Interested Party), Kiptieu Debs (2nd Interested Party)

Legal area(s): Judicial review, constitutional law, criminal procedure, private prosecutions, company law, abuse of process

Tags (indexing): certiorari, supervisory jurisdiction, private criminal summons, Attorney General suit, DPP powers, constitutional supremacy, locus standi, actio popularis, Companies Act 2009, Criminal Procedure Act 1965, Criminal Procedure Act 2024

Legal representatives (as recorded by the court)

For the Applicant: SK Koroma, RA Nylander, R Payne

For the Respondent: Leon Jenkins-Johnston, R Mahoi, MN Koroma, M Mansaray

For the 1st Interested Party: YI Sesay (State Counsel)

For the 2nd Interested Party: Ms ES Banya

Legal Areas

Judicial review, certiorari, supervisory jurisdiction, magistrates court, private criminal summons, company as complainant, constitutional control of prosecutions, Attorney General and Minister of Justice, Director of Public Prosecutions, locus standi, actio popularis, Companies Act 2009, Criminal Procedure Act 1965, Police Act 1964, Law Officers Act 1965, constitutional supremacy, abuse of process, fair trial safeguards, Criminal Procedure Act 2024.

Headnote (case digest)

The applicant, a shareholder (10 percent) of a company, faced private criminal summons proceedings for forgery in the Magistrates Court after the DPP advised that the dispute was civil and parties should seek civil redress. The applicant sought judicial review, principally certiorari to quash the magistrates proceedings and a stay. The Attorney General and Minister of Justice was joined, and a second interested party, also affected by similar privately issued summons practice, was joined.

Fisher J held that the complaint was amenable to judicial review because the High Court’s supervisory jurisdiction over inferior courts includes ensuring that criminal proceedings are lawfully instituted, and if instituted unlawfully the magistrate court lacks jurisdiction. The court held that a company incorporated under Sierra Leone law has no lawful basis to institute criminal proceedings in its corporate name, and that the private criminal summonses in issue were not authorised and were not notified to the Attorney General or the DPP as required by the constitutional scheme. The court granted certiorari quashing the proceedings against the applicant and the second interested party, and ordered costs.

Procedural history

Originating Notice of Motion for judicial review filed 16 January 2025 seeking certiorari to quash magistrates proceedings and an interim stay.

Leave granted 11 February 2025, Attorney General and Minister of Justice added as a party.

21 February 2025, 2nd interested party added, stay of proceedings in the magistrates court granted.

Statements of case filed by applicant and respondent, interested parties relied largely on principal parties’ positions.

Material facts (as found or summarised by the court)

The applicant claimed he was a shareholder and had been running the business with the main shareholder’s approval until disputes arose after the main shareholder’s death.

Competing reports were made at CID, files were sent to the DPP. The DPP advised the matter was civil and parties should seek civil redress.

Notwithstanding the advice, the company’s solicitors caused a private criminal summons to be issued, leading to the applicant’s arraignment and ongoing proceedings in Magistrate Court No 2.

The respondent asserted it could institute the matter, that forgery can be pursued criminally, and that private solicitors can institute private criminal summonses on behalf of a company.

The 2nd interested party described repeated privately issued summons conduct in her own matter, including reissuance after an earlier summons was thrown out, and alleged abuse and embarrassment.

Issues

Amenability: Is the applicant’s complaint amenable to judicial review?

Corporate prosecution: Can a company incorporated in Sierra Leone lawfully institute criminal proceedings in its corporate name?

Constitutional control: Can criminal proceedings be instituted without reference to, authorisation by, or notification to the Attorney General and Minister of Justice (and by extension the DPP), given the constitutional provisions governing prosecutions?

Holdings

Amenability to judicial review: Yes. The court treated the substance as a supervisory challenge to the lawfulness of the magistrates court continuing proceedings allegedly instituted unlawfully, which goes to jurisdiction and engages section 134 supervisory powers.

Company instituting criminal proceedings: No. The Companies Act 2009 framework provides for civil actions and remedies, not corporate criminal prosecution in the manner attempted, and the company’s M and A did not supply any basis either.

Proceedings without reference/authorisation: On the facts, the summonses were unlawful because they were not authorised in accordance with the constitutional structure and were not notified to the Attorney General or the DPP, especially where the DPP had advised the dispute was civil.

Court’s reasoning (structured)

A. Seriousness of jurisdiction and supervisory control

The judge treated jurisdiction as foundational. If proceedings are instituted unlawfully, the magistrate court is deprived of jurisdiction, and continued proceedings are a nullity. This justified High Court intervention by certiorari under section 134.

B. Amenability, function over form

Although the respondent argued it was a private entity not subject to judicial review, the court reframed the complaint: the challenge was to the lawfulness of instituting and maintaining criminal proceedings in a way that engages public law controls over prosecution, and to the magistrate’s continuation of such proceedings. The court adopted “function not form” reasoning, drawing on authorities that allow review where conduct is woven into public regulation or public duty.

C. Companies Act 2009 does not create corporate prosecutorial power

The judge examined Part 11 of the Companies Act 2009 on actions by or against companies, noting that remedies and derivative mechanisms are civil in nature (injunctions, declarations, civil relief). The judge concluded there is no statutory basis for a company to institute criminal proceedings in its corporate name, including against a shareholder in the manner attempted.

D. Constitutional architecture of prosecutions

The court placed primary weight on section 64(3) of the 1991 Constitution (all offences prosecuted in the name of the Republic shall be at the suit of the Attorney General and Minister of Justice or a person authorised by him) and the DPP’s powers under section 66(4) and delegation under section 66(5), subject to section 64(3). The court also referenced statutory mechanisms for control of proceedings (nolle prosequi under the Criminal Procedure Act 1965) and police prosecutorial authority under section 24 of the Police Act 1964.

E. Private criminal summons practice and fair trial safeguards

A substantial portion of the reasoning is policy and safeguards driven. The court contrasted police investigated prosecutions (statements, exhibits, advice, disclosure safeguards) with private summons practice, which in the judge’s assessment can be used oppressively, including bench warrants on first non appearance, limited disclosure, and tactical incarceration, raising fair trial concerns (section 23 Constitution). The court signalled that magistrates should be vigilant and consider stays for abuse of process.

F. Criminal Procedure Act 2024 (forthcoming) and constitutional consistency

The court noted commencement arrangements bringing the Criminal Procedure Act 2024 into force later, and discussed its express mechanism allowing private complaints. The judge considered that, even under a private complaint model, constitutional consistency requires notification to the Attorney General and or the DPP so they can exercise constitutional powers to take over, continue, or discontinue proceedings. The court suggested an administrative or practice direction mechanism (for example via the Deputy Assistant Registrar or Chief Justice practice directions) to ensure notifications.

Ratio decidendi (binding core)

Where criminal proceedings in a magistrates court are arguably instituted unlawfully, especially in breach of constitutional provisions governing prosecutions, the High Court may exercise supervisory jurisdiction by judicial review and certiorari to quash the proceedings as a jurisdictional nullity.

A company incorporated under Sierra Leone law has no lawful basis in the Companies Act 2009 (or its M and A) to institute criminal proceedings in its corporate name, and such proceedings are liable to be quashed.

Criminal proceedings prosecuted in the name of the Republic must comply with the constitutional scheme that places prosecutions at the suit of the Attorney General and Minister of Justice (and the DPP’s constitutional powers), so privately issued summonses without the necessary constitutional linkage (authorisation and or at minimum notification enabling constitutional control) are unlawful.

Obiter dicta (persuasive guidance)

Strong judicial warnings about the systemic risks of private criminal summonses being used as instruments of oppression, including risks to fair trial rights and public confidence.

Proposed procedural reforms and notification mechanisms to align private complaint processes with constitutional requirements, including potential practice directions or legislative amendment.

Disposition and orders

Certiorari quashing the magistrates proceedings titled “Pioneer Power Engineering Company (SL) Limited v Zhou Wenjie”, with discharge of the defendant (the applicant) forthwith.

Certiorari quashing the proceedings titled “Adama Jalloh v Kiptui Debbs”, with discharge forthwith.

Costs awarded against the respondent in favour of the applicant and the 1st interested party, and against Adama Jalloh in favour of the 2nd interested party, to be assessed pursuant to the High Court Rules 2007 (Order 57 referenced by the court).

Significance

This decision is a major High Court statement on the constitutional control of criminal prosecutions in Sierra Leone, the limits of “private summons” practice, and the inability of a company to prosecute criminally in its corporate name. It also anticipates implementation issues under the Criminal Procedure Act 2024 and presses for notification safeguards to preserve constitutional oversight and fair trial guarantees.

Cases and statutes or other laws cited in the judgment (as recorded)

A. Sierra Leone Constitution and statutory materials

Constitution of Sierra Leone, Act No 6 of 1991, including sections 15, 23, 64(3), 66(1), 66(4), 66(5), 124, 134, 170, 171(15), and references to section 129.

Companies Act No 5 of 2009, Part 11 (sections 255 to 264), with specific discussion of sections 255, 256, 258, 259.

Criminal Procedure Act 1965 (including sections 10, 12, 16, 30, 44, 45, 46(2), 80, 144(2) as referenced).

Criminal Procedure Act 2024 (sections 18 and 19 discussed), and Criminal Procedure Act (Commencement) Regulations 2025 (commencement date referenced by the court).

Police Act 1964 (section 24).

Law Officers Act 1965 (section 5 referenced).

Law Officers (Conduct of Prosecutions) Instructions 1965, Public Notice No 33 of 1965 (PN No 33).

National Social Security and Insurance Trust Act 2001 (section 33 mentioned).

Anti-Corruption Act 2008 (section 89(1) mentioned).

High Court Rules 2007 (Order 18 rule 6, Order 57).

Forgery Act 1913 (mentioned).

Offences Against the Person Act 1861 (sections 18 and 20 mentioned).

Halsbury’s Laws of England (3rd edition, volume 6, pages 440 to 443, and 4th edition, volume 44 statutes, paragraph 933).

B. Sierra Leone cases

Celtel (SL) Ltd and Registrar of Companies House v Alie Basma Civ.App. 9/2009.

Union Trust Bank v Sierra Construction Systems Misc.App. 032/20.

The Peoples Movement for Democratic Change (PMDC) and Secretary General for PMDC v Sierra Leone Peoples Party (June 2007, unreported).

Mohamed M’bakui and another v The State Misc.App. 5/2016, SLCA 1150.

The State v Adrian Joscelyne Fisher SC.2/2009.

State v Justice M.O. Taju-Deen ex parte Harry Will SC misc 3/99 (unreported).

Lansana Kainchallay and 64 others CC.395/15.

PC Dr Alpha Madseray Sheriff v Attorney General and Minister of Justice SC No 3/2011.

Sierra Leone Association of Journalists v Attorney General and Ors SC.1/20.

Chanrai and Co v Palmer 1970 to 1971 ALR SL 391.

C. UK and other common law authorities

Council of Civil Service Unions v Minister for the Civil Service (cited as 1992 4 All ER 97).

Ridge v Baldwin [1964] AC 40.

R v Panel on Takeovers and Mergers, ex parte Datafin [1987] QB 815.

R v DPP (cited as 1995 1 Cr App Rep 136).

R v DPP and Others, ex parte Timothy Jones (cited as 2020 QBD 3088/99).

R v CPS (cited as 2012 UK SC 52).

R (on the application of Holmcroft Properties Limited) v KPMG LLP [2018] EWCA Civ 2093.

R (Aegon Life) v Insurance Ombudsman Bureau [1994] 1 CLC 88.

R v Independent Broadcasting Authority, ex parte Whitehouse (1984) Times 14 April.

Ware v Regent’s Canal Co (1858).

R v Rent Officer and another, ex parte Muldoon [1996] 1 WLR 1103.

Secretary of State for the Home Department v Nasseri [2009] 1 All ER 116.

Connelley v DPP [1964] AC 1254.

R v Beckford [1996] 1 Cr App R 94.

R v Derby Crown Court, ex parte Brooks [1985] 80 Cr App R 164.

Sussex Peerage Case (1844) 11 CL and F 85.